Images

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

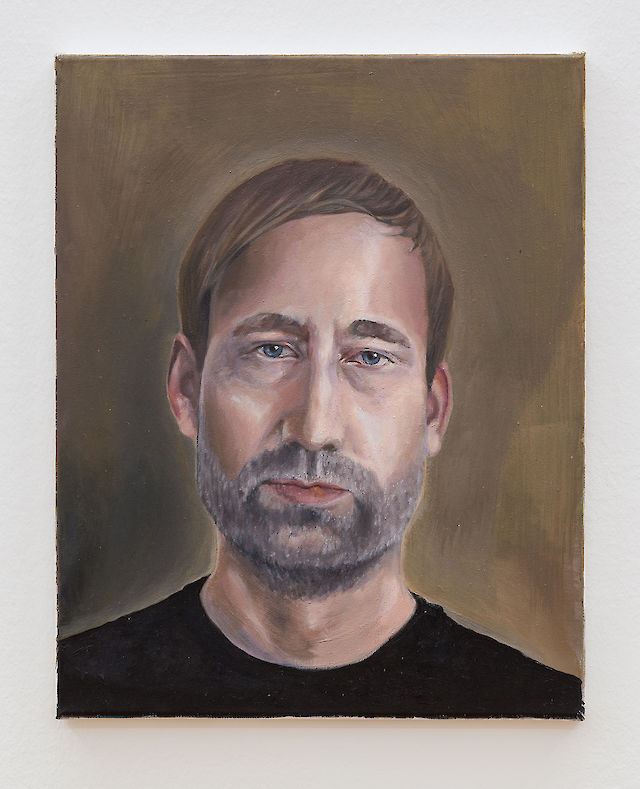

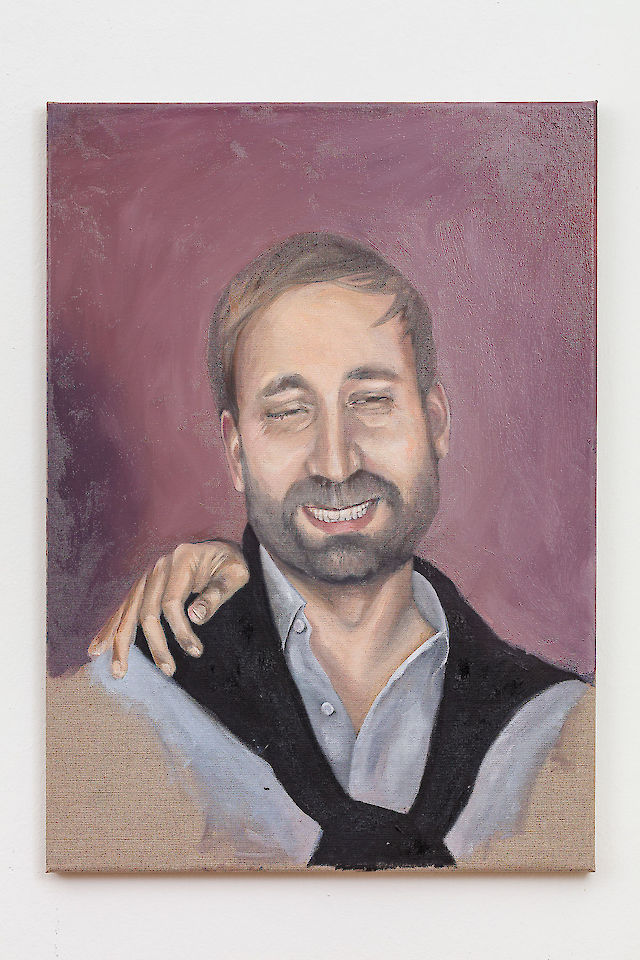

Nina Beier, Oliver Croy (1), Oil on canvas, 50 × 40 cm 2019

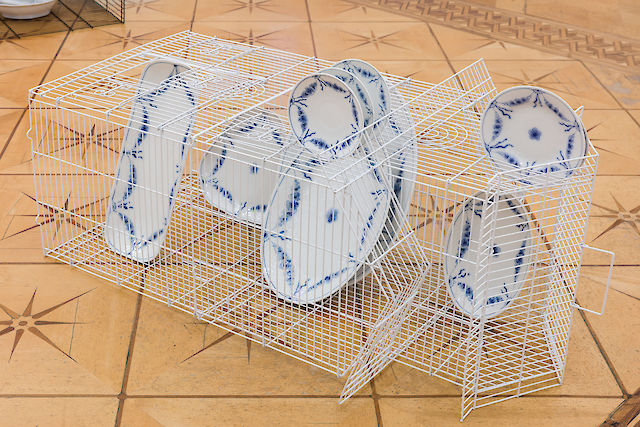

Nina Beier, Empire, 2019, ‚Empire‘ Porcelain dinnerware by B&G/Royal Copenhagen and metal wire bird cage, 94 × 44 × 33 cm

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, Empire, 2019, ‚Empire‘ Porcelain dinnerware by B&G/Royal Copenhagen and metal wire bird cage, 54 × 43 × 63,5 cm

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, Empire, 2019, ‚Empire‘ Porcelain dinnerware by B&G/Royal Copenhagen and metal wire bird cage, 49 × 98,5 × 45 cm

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, Empire, 2019, ‚Empire‘ Porcelain dinnerware by B&G/Royal Copenhagen and metal wire bird cage, 37 × 35 × 25,5 cm

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, Fingers Crossed Crossed Fingers, 2019, Leather glove, military decorations, commercial pins, religious symbols and jewelry, 11,5 × 19,5 cm

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

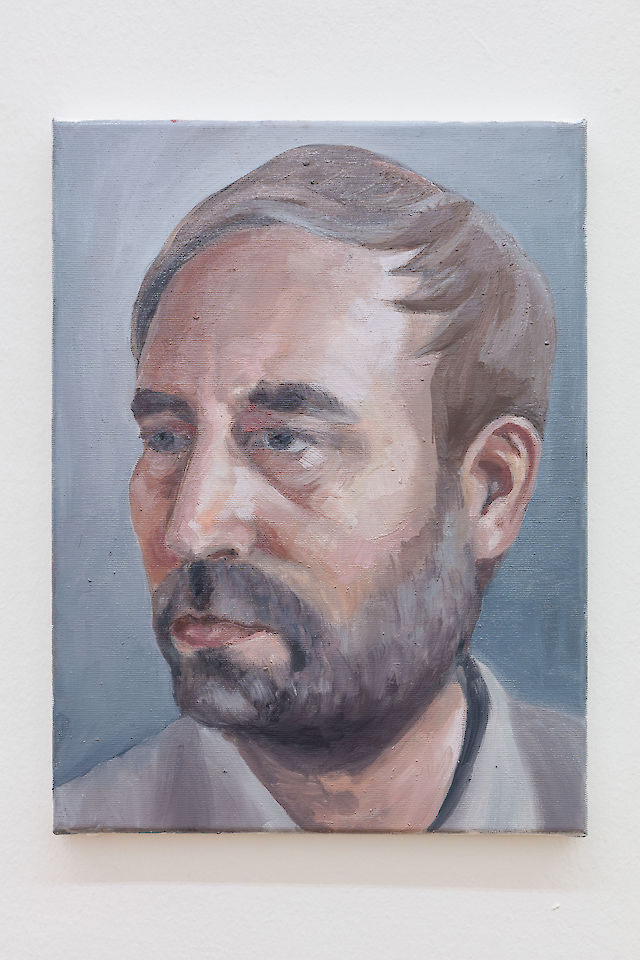

Nina Beier, Oliver Croy (2), Oil on canvas, 30 × 40 cm 2019

Nina Beier, Plug, 2019, Ceramic sink and handrolled cigar, 58,5 × 43,5 × 33 cm

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen, Vienna, 2019

Nina Beier, Oliver Croy (3), Oil on canvas, 50 × 40 cm 2019

Nina Beier, installation view European Interiors II, Croy Nielsen / Café Milano, Vienna, 2019

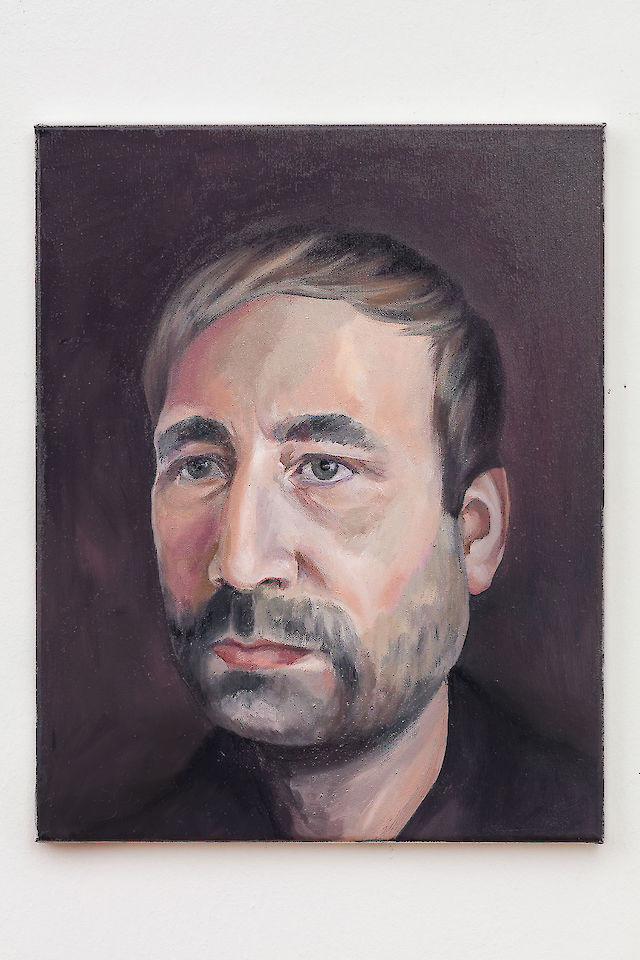

Nina Beier, Oliver Croy (4), Oil on canvas, 70 × 50 cm 2019

Photos by Kunst-dokumentation.com

Press Release

Objects that have a messy relationship to some original are regular features in Beier’s practice. How they resemble or differ from their references varies, but the differences can reveal more than just authentic versus copy. In the case of remote control luxury cars that Beier previously repurposed: they are electric, while real Range Rovers are decidedly not. The real hair wigs that Beier installed, spilling out of the miniature truck windows are copies in their own right. Generally grown by women in China and India, the cut hair is then bleached, dyed, and coiffed into popular western styles.

For an object to invite copying, it must first achieve some level of cultural cachet. Its copies can paradoxically reveal the multifaceted and often troubling ways that this type of value is constructed. In taking up these objects, Beier nudges us into reckoning with our relationship to the tropes that cause us to associate things with power, security, prestige or happiness. Perhaps more unsettlingly, this mental audit can cause these associations to reverse themselves.

For her fourth exhibition at Croy Nielsen, Nina Beier tackles some messy copies and creates some others herself. Pieces of collectable porcelain dinnerware inhabit birdcages that imitate man-made architecture. Installed on the gallery’s parquet flooring, the antique china doesn’t seem out of place in this formerly domestic space. Each hand-painted plate or vessel belongs to a series called Empire that was produced by Royal Copenhagen. Porcelain ceramics imported from China became coveted status symbols in Europe as early as the 14th century. They were quickly and widely copied, yet European craftspeople couldn’t match the quality of Chinese exports for another nearly 400 years.

Hung on the surrounding walls are portraits of one of the gallery’s founders – Oliver Croy. Painted by Beier in a style that telegraphs how earnestly the artist took her charge of portraying her gallerist, they are good likenesses. If you want to check for yourself, just have a peek into the offices and see the original in the flesh.

By placing things into an uneasy state of cohabitation, I feel like Beier causes them to become more honestly themselves – as if an exhibition could also be group therapy for wayward commodities. Whether this is the case for the art dealer surrounded by paintings of himself is harder to say, but the short circuiting of the dynamic between a gallerist and the works they exhibit reveals something interesting about the machinations of art.

Rather than exempting herself, Beier instead draws a fascinating and humanizing line between her paintings and the objects she appropriates. In doing so, the subjectivity of the knock-off is illustrated anew. Some deviations from the source might just be the predilections of those who created the reproduction shining through. Just as a portrait painter can choose to focus on a few favored features to describe a subject, so can the handbag forger. That these choices are inevitably influenced by the power structures that enabled them is something that we are left to grapple with on our own.

– Patrick Armstrong