Images

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

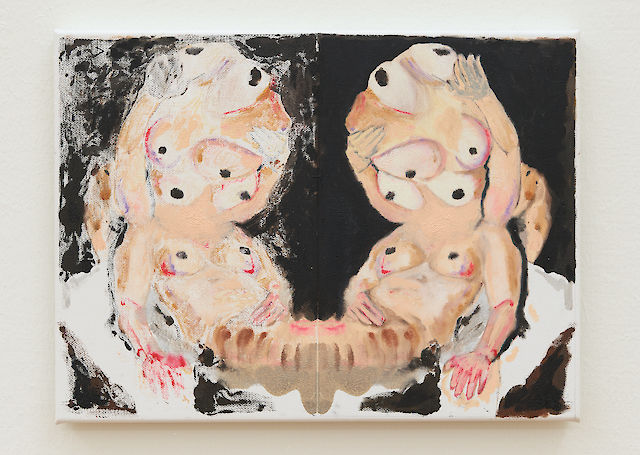

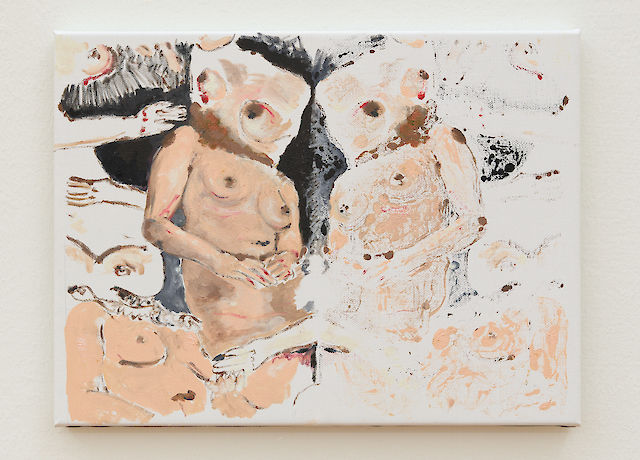

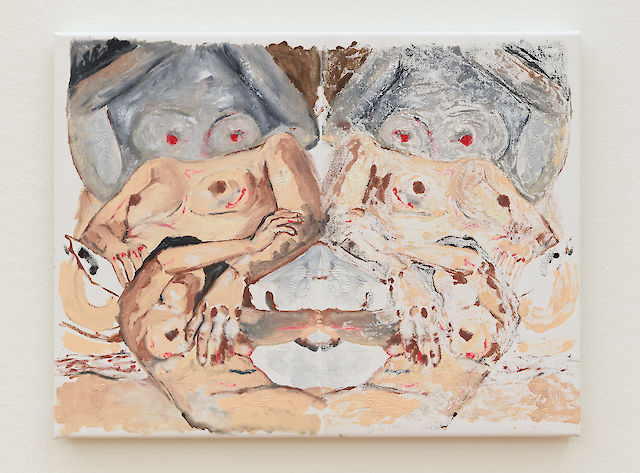

Marlie Mul, Folded Painting #7, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 29 × 39 × 2.5 cm

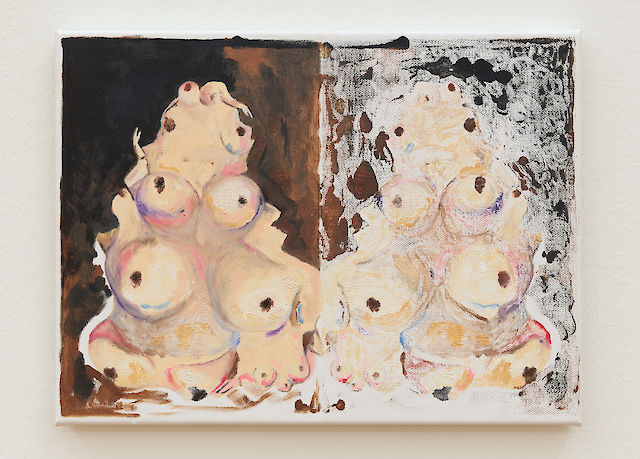

Marlie Mul, Folded Painting #8, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 29.5 × 39 × 2.5 cm

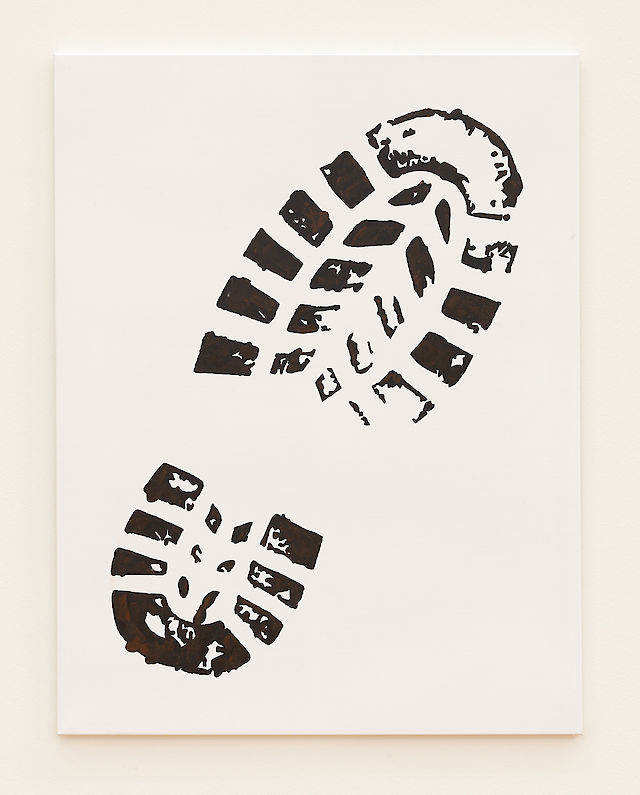

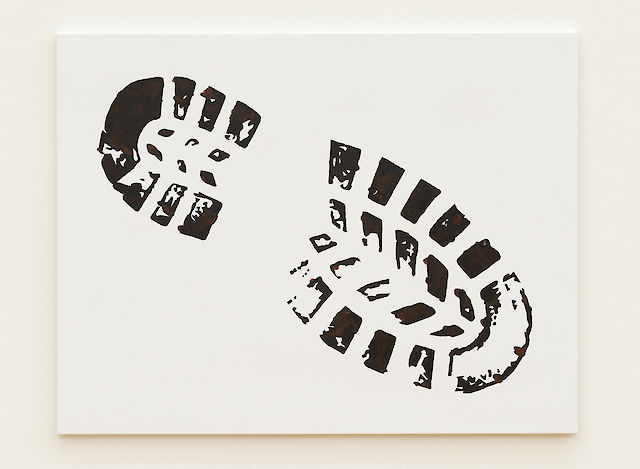

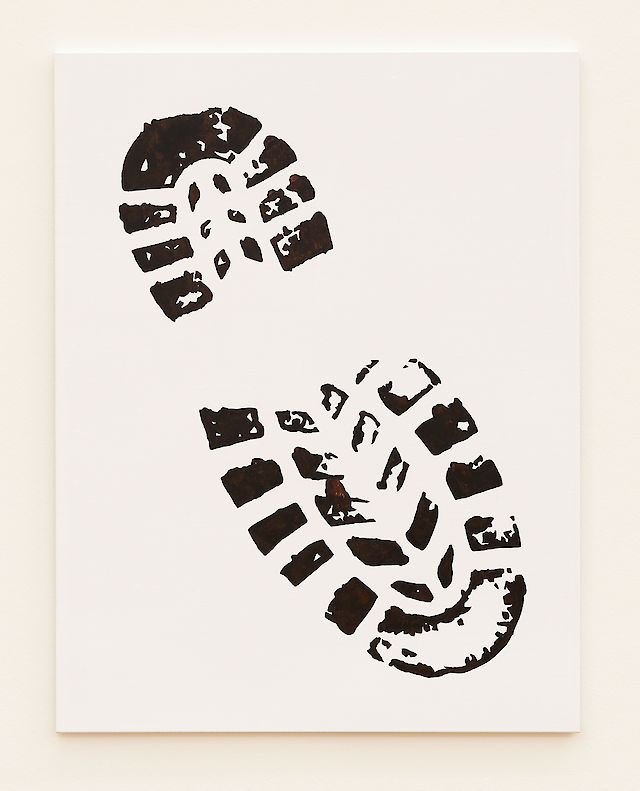

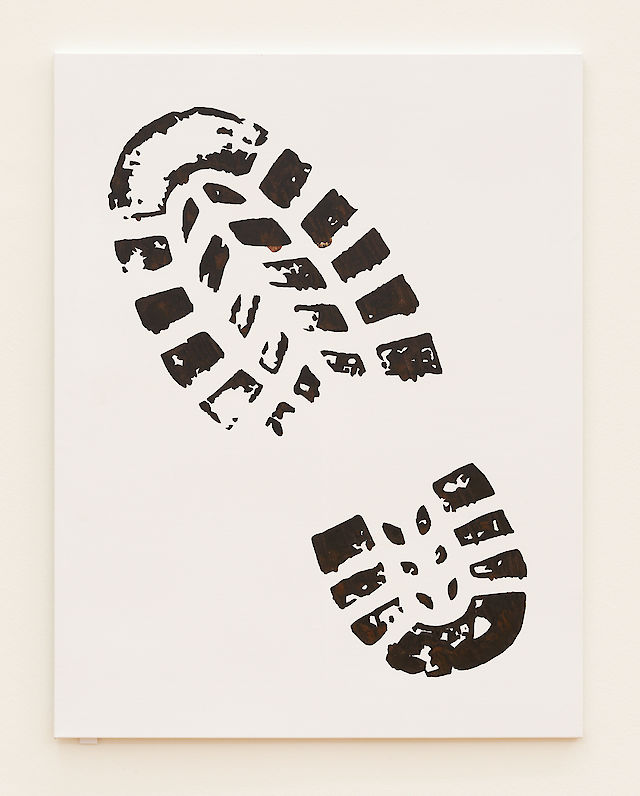

Marlie Mul, Shoe Stamp #1, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 140 × 108 cm

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

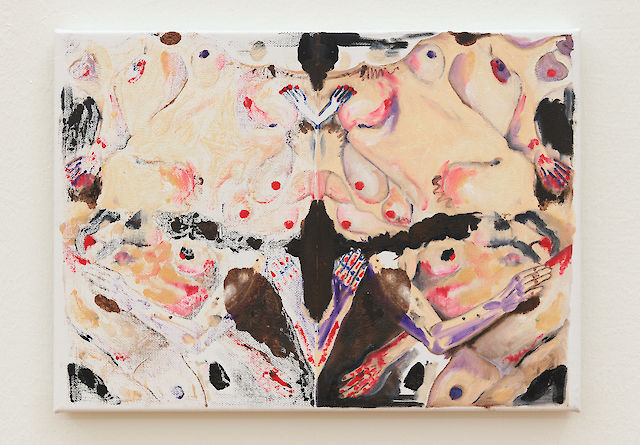

Marlie Mul, Folded Painting #6, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 29 × 40 × 2.5 cm

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

Marlie Mul, Folded Painting #2, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 30 × 40 × 2.5 cm

Marlie Mul, Folded Painting #9, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 34 × 44 × 2.5 cm

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

Marlie Mul, Shoe Stamp #4, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 140 × 108 cm

Marlie Mul, Shoe Stamp #2, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 140 × 108 cm

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

Marlie Mul, installation view Booby, 2017

Marlie Mul, Shoe Stamp #3, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 140 × 108 cm

Marlie Mul, Folded Painting #5, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 33 × 45 × 2.5 cm

Photos by Pascal Petignat

Press Release

Boobies often come in pairs, and not just physically: a booby means both a breast and a stupid, gullible or reckless person. The humble, light-hearted word booby, thus carries associations of big and serious topics such as gender politics, intellect and personal responsibility, which alongside labour have been recurrent themes in the work of Marlie Mul. These are timely topics: we are currently in a supposed crisis of personal responsibility, with everything from obesity to unemployment being blamed on the actions of feckless people. According to this logic it is the individual who lets society down, not the other way around – a view that has been promoted by liberal politicians and pundits to avoid tackling structural or social inequalities.

The most visible arena in which personal actions are politicised as socially irresponsible has formed around smoking, the subject of a series of digital prints on silk and cigarette stuffed air vents that the artist made in 2012. The silks show billows of smoke, printed as mirror images, each side personified with identical pairs of eyes that stare at one another suspiciously. Sometimes she includes a cartoon infant, puffing away on a cigarette. Mul points to an ethical confusion: what are presented as issues of self-control are managed through guilt, shame and social conformity, particularly when it comes to women’s bodies. Liberal governments have invented a concept of individual responsibility not just to blame their citizens, but a means of controlling them too.

Mirroring, conformity, reproduction and the ready-made – beyond these there is a further problem of copying that in Mul’s current exhibition Booby, troubles the very definition of responsibility. Here we shift from health to the self, as she explores her roles as woman and artist. In the paintings, the artist’s body appears fractured and doubled, her image both personal and reduced to recognisable poses: woman here is socially and representationally constructed. Women are held culpable for bodies whose images they do not control, according to values they did not create and through obligations to the family, child and social reproduction. As an individual, she remains unknowable, even as her body and actions are subject to surveillance. Strangely, in order to take ownership of and responsibility for her own image, Mul cedes control further. She chooses to work in a medium that is unfamiliar to her and by folding each painting she engages in a process of hand printing that introduces the element of chance as the imprint might not work and the original may be ruined. Rather than drawing upon her creative and intellectual skills to finish the image, she embraces the stupidity of merely filling in the space. Being responsible is commonly thought of as being in control of your actions and knowing what you are doing. But as political thinker Thomas Keenan has written, responsibility only comes with the ‘withdrawal of the rules of knowledge on which we might rely … It is when we do not know exactly what we should do.’1 Doing what you are told, doing what you feel you ought to, mimicking the views of others, shifts all the responsibility away from the self and provides a preexisting alibi for our actions. Counter-intuitively, being responsible, following Keenan’s line of thinking, means acting blindly, without preconceptions or received opinion, as if stupid, otherwise nothing is risked. Stupidity, cluelessness, become surprisingly good ways to assert autonomy and avoid social coercion.

It might seem odd then, and particularly stupid, that the artist has chosen to work in that most bourgeois of forms, the classical female nude. Between Mul’s paintings are printed images of shoe prints, which might be either stamping something out or kicking down a barrier – they hang ambivalently between authority and rebellion. In using such a passé art form as the nude, Mul deliberately courts stupidity and risk, rather than the cool role of the rebel: few things are more bourgeois and conventional than rebelling against the bourgeoisie. Instead of the stamp of the rebel boot, Mul employs her own stamping technique in printing and claiming for herself the highly mediated female image. With Booby, the artist takes seriously, with all the irony that entails, the idea of responsible stupidity.

Paul Clinton is a writer and curator based in London, UK. In 2015 he curated

the exhibition ‘duh? Art & Stupidity’ at Focal Point, Southend-On-Sea.