Images

From whose ground heaven and hell compare

Olga Balema, Georgina Braoudakis, Elaine Cameron-Weir, Georgia Dickie, David Flaugher, Aleksander Hardashnakov, Jason Matthew Lee, Jared Madere, Carlos Reyes, Eric Schmid, Ben Schumacher, Andy Schumacher, Luke Schumacher

Organized by Ben Schumacher

13. 6. – 26. 7. 2014

Installation view From whose ground heaven and hell compare, 2014

Installation view From whose ground heaven and hell compare, 2014

David Flaugher, Lisa’s Potpourri, 2014, Wax, candle wicks, plastic, lights, 10 ø 30 cm

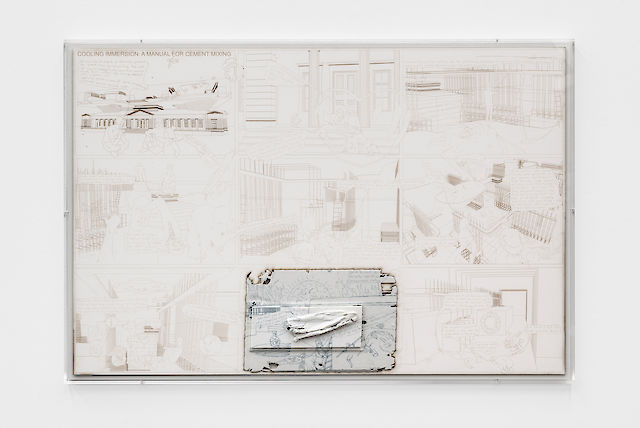

Andy Schumacher/Ben Schumacher, Untitled, 2014, Laser cardboard (drawing) and 3D print, framed, 63 × 95 × 3 cm

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (mushrooms cry, 11:48), 2014, Laser etched mushroom, ø 25 cm

Jason Matthew Lee, Iciclesmadeofsweat, 2014, Spray painted pay phone, 50 × 20 × 15 cm

Jared Madere, Untitled, 2014 (detail), Salt, funerary arrangements, ink, Dimensions variable

Jared Madere, Untitled, 2014 (detail), Salt, funerary arrangements, ink, Dimensions variable

Installation view From whose ground heaven and hell compare, 2014

Olga Balema, Subscribing is better, 2013, Plastic box, steel, hoses, water pump, textile, 74 ø x 64 cm

Installation view From whose ground heaven and hell compare, 2014

Aleksander Hardashnakov, The Trap Room 4, 2014, Colored pencil, gesso, oil, on scratched canvas, board mounted to panel (hardware), 46 × 61 cm

Aleksander Hardashnakov, The Trap Room 2, 2014, Colored pencil, gesso, oil, on scratched canvas, board mounted to panel (hardware), 46 × 61 cm

Installation view From whose ground heaven and hell compare, 2014

Installation view From whose ground heaven and hell compare, 2014

Installation view From whose ground heaven and hell compare, 2014

Press Release

Say our universe is only one region of cosmological fallout among many, from some great cosmogenetic event—not the first or only cosmogenetic event, but a cosmogenetic event. Like the popular imagining of the Big Bang, this event is unique and has specific consequences, but it also has a generic aspect, without pretensions to absolute originality or primal origination. The different regions are characterized by disparate determinations of elemental matter and energy (or their analogues); correspondingly, motion, change and continuity occur differently. How far could we take this? Our most fundamental characterizations of the basic “stuff” of reality—e.g. space and time, matter, substance, waves and particles—as well as our most fundamental categories for understanding their relations—e.g. cause and effect, chance and necessity, change and continuity, and so on—might not even apply or anyway apply only in asymptotic approximation to other cosmological regions. The perspective we have developed on this reality is complicated not only by the fact that there are other realities (and other perspectives) of disparate developmental dispositions, but also because its cosmo-logic does not consist simply of the innate and eternal determinations of self-identical “matters.” First off, it can be said that things and their systematic interrelations are the results of earlier spontaneous developments. They cannot now be separated out from those processes, as if a moment had passed wherein the privilege of the constitutive interactivity of the disparate gave way to the privilege of the thing. For even that separation would coincide with the interactive process and separateness would be a result of its development. The thing (or the system of things) would be, not a passive unity, but the living unity of forces continuing along a certain trajectory. Moreover, the affinity in the coming-together of the thing and the violence and adversity of its separation out of the mix would be one and same (as we say: “depending on perspective,” which is a force of preeminent concern here). So, secondly, the immanent cosmo-logic of this reality involves the ongoing realization of spontaneous developmental interactions between disparate forces, energies and matters—or rather, between irreducibly, incomparably unique cosmic happenings. Rest and stability are not passive moments in which privilege must be accorded to that moment of which this one is the repetition, or to that previous moment from which the present one continues more or less the same. Both change over time and periods of relative stability, perseverance, and even rest are constituted and reconstituted through a repetition or endurance of the interactions immanent to the developmental event; or, in other words, through a micrological continuity of the spontaneous interactions characteristic of the macrological event (without placing undue emphasis on either of these cosmological moments). Moreover, there is no telling how or when some interaction internal to this “system” or between it and another—which, similarly unique, may be immanently related through a kind of marginally porous border and/or cosmogenetic lineage—may set off another spontaneous macrological event.

In beginning with this brief narration, it seems that we have tried to complicate the simple togetherness or duration of what it is that persists here, now, immediately apparent to the senses. The imperative of this apparent complication occurs insofar as this very togetherness, seemingly of a stable nature, is posited as the tensed and provisional result of what could be described, not as a logically necessary process, but as a spontaneously necessitated happening between elements of radical difference. What now appears as the natural affinity of the necessarily related, then, would in fact result from the competing tendencies of adversity (e.g. separation and infiltration) and compatibility (e.g. growth!) and contain the tension of such interactions in its really provisional, uncertain systematicity and logically abstractable togetherness. Insofar as we retain, reproduce and reverberate with the effusive back-and-forth of this legacy, it is tempting to view our individuated division out of the fray as a kind of ignorance, self-preservative functioning, or (what seems more damning) fear vis-à-vis the historical drama that is effectively living us. From this view, simplicity might be seen as a kind of myth—a feeble attempt to abstract ourselves from the principle of spontaneity that both determines and undermines the constitution of “moments” of existence. Our simplifications could be seen as weak and one-sided reiterations of aspects we are thrown into by virtue of our contingent positioning. We try to fix the determinacy of that contingent positioning—to see “life” in terms of our life—rather than interpreting its determinacy as that of life and, in a problematic sense, for us as the living. Although we sense that we are always at a marginal front of the drama, it remains the case that we are the composition of that front.

On the other hand, willful complexity and confusion appear here as a superficial response to the promiscuous undertones of the mytho-logical simplicity through which diverse individuals and societies are grouped together. The basis of that response might go as follows: our way of grouping what are complex and different matters grasps their composition as a simple unity of independent matters whose relatedness-in-difference is taken as subsidiary or incidental. In privileging, or taking as primary, the atomistic identity or unity of the different, we project the abstract perspective of human observation onto matter. When we then consider the human subject as a composite of individual nerve cells, we simultaneously conceive matter through the veil of our own perspective and posit that image as a generative principle to which all else reduces—i.e. the atomistic matter is generative, but generates nothing but what ultimately reduces to its own primary identity, which is interpreted from the start in accordance with the projection of our own abstract perspective!

However, the scrupulous critic continues, it makes equal theoretical sense to view matter as generated, whether in its inherent composition or as the spontaneous continuity of a thing perpetually constituted and reconstituted by its primordial conditions of difference—i.e. as the matter of a differential relation between unique forces and energies. We can, of course, view simple, ready-to-hand (apprehensible), logical images as useful, empirically observable, and so on. But, on its part, simplicity is an accomplished simplicity and itself a kind of force—an abstract and abstracted force—as little undoable as it is unproblematic. We can view ourselves as a complex of individual nerve cells which, however, effectively retain the unity of simpler cells, which retain the simplicity of molecules, atoms, and so on—all along retaining the view of ourselves as abstract independents isolated in our void. But even the abstract imagination cannot avoid the sense that this is a tensed separation (somewhat in the manner of an inherited responsibility), and that our separateness is marked through the very same force of tension separating the logical abstraction from the qualitative array of (sensory-perceptual) objects. For example, it is shared experiences and histories, and their repeated application and communal circulation, that naturalizes the methods and concepts of a discourse—which is not to place discourse on one side and reality on the other, but to designate the principal dialogues of question and answer, call and response, repetition and adversity, through which “reality” is held together and thrust forward. The simplicity of thought is inextricable from a continuous process of simplification, bound up with complex relations to the expenditure of time and energy which are interpreted (i.e. in a simplifying manner) in the course of that very relation. Thus, what is here at issue is not only the treacherous complexity of what merely appears simple, but the complexity of accomplished simplicity as such.

Consider Heidegger’s manner of calling into question the conventional approach to language:

“Man speaks.” This idea evokes the sense that language is: 1) something spoken by human beings, as their activity; 2) a means of giving interpersonal expression to personal thoughts, feelings and experiences, i.e. a universal medium of communication between speakers; and 3) a form of “presentation and representation of the real and the unreal” (Heidegger 190). All of these approaches to language seek to characterize its universal character—i.e. the fundamental system underlying all particular instances of language and connecting them together—as well as its function, or (more broadly) what it does. They treat language alongside corresponding perceptual, cognitive and motor capacities that together are said to constitute the human being as such. And just as language is used to logically represent and qualitatively describe other phenomena, it is further used to logically break down and represent both isolated acts of linguistic expression and the sociohistorical processes through which they change over time. All of this is correct, says Heidegger in his “Language” lecture. But the truth is that “Language speaks”— “Sprache spricht.”

Heidegger thus makes a “beginning” of his lecture with the tautological proposition “language is language.” The tautology appears obvious and self-evident—a bare assertion of language’s equality to itself—such that, if anything, it can only function as a beginning (and a particularly unhelpful one at that). But in fact, we easily see that it is no more a beginning than it is a mere result; for it says that, throughout all that is said and done, language continues in its speaking just as it begins of itself, regardless of whatever affects or intentions, effects or purposes have been expressed, communicated or accomplished in between. So, similarly, we can say that “language is language” is an empirical observation and/or a logical proposition, suggesting the simple self-identity of the phenomenon of language with itself; but this remains inattentive to what the proposition is actually saying in its circularity, a circularity that precedes, supersedes and proceeds all throughout the specialized disciplines of logic and empirical science.

Of course, the logical structure of the proposition is familiar. We can take the “is” as a sign of equality, saying that language is identifiable as language. Even if we were to replace the word “language” with a nonsenseword or a simple “X,” we would remain with the formula by which anything is identified and thereby addressed (e.g. in rational thought and language). But we are left the difficulty whether it is the address or the thing addressed that is primary in the identity—for if it is both then the very concept of identity appears as a tensed simplification. The difficulty is especially prevalent in the case of language because it is in itself a mode of address; and yet that address invariably speaks toward, or is solicited for the presentation of, things. It is only in rarefied form that language addresses itself—and even then language is sent out in particular acts meant to speak to the universal ground from which they emerge. Thus, the abstraction of language as a universal task or objective function makes of it a kind of thing, when language of itself presents itself differently: “language is language.” To interpret this as a logical proposition is a simplification, or the complex situation of a misinterpretation, fixating on a passive relation of terms that is not language’s own, however readily it may provision itself toward those purposes (i.e. by speaking “logically”).

The proposition “language is language” establishes speaking as a type of relationality, calling us into its active sense without assigning us a position in it. But we can only respond to such an invitation on the condition that we already abide in the openness of such a relation—for we can very well move from a condition of relatedness toward the statement of identity, but no merely self-related identity could ever overcome its own passivity. The proposition of the original relation of language thus calls our accomplished statement of language’s logically necessitated identity with itself back within the originality of the relational address which stands before and supersedes all established relations. The seemingly tautological proposition thus takes us on a little tour of sorts. We might say that it establishes us within a mode of comportment, the faithful progeny of a perpetual re-beginning: never where we think to have located ourselves; never finding anything we do not have already. For just when we thought we were speaking about language, it becomes clear that speaking is occurring despite ourselves—in a sense, language itself is either speaking out or beckoning to us, as the ones who are capable of speech. For if we had language, there would be no sense in speaking its name twice. The question then arises: do we have it partially, such that we need to continue to make it appear by speaking its name; or do we have language in excess, as a freely given speaking? But either of these ways of looking at language misses the point. For each of these places the human and language in an abstract, algebraic or even geometric relation, effectively deemphasizing the “is” which goes between (or relates) the related, when the question is really why, even when we seem to be speaking about language, we are always destined to continue speaking—i.e. we cannot simply (transitively) speak language and have done with it or (intransitively or reflexively) do language, and similarly have done with it. Heidegger remarks that “The speaking does not cease in what is spoken. Speaking is kept safe in what is spoken” (191−192). In acts of speaking, humans respond to the relation in which they are already held together by the very fact that they can be said to have a language or some language (and it is always a particular manifestation of language that is had). It is this relation in which the human is placed with language all throughout acts of speaking, and out of which the relation to it (in the sense of the logical formula) is only provisionally differentiated, that is vital to the speaking of language itself.

We enter into the always strange and unfamiliar territory of language, as if for the first time, as soon as we begin to analyze the manner in which its components appear to us. Various elements associated with linguistic expression can be distinguished through empirical investigation. In fact, a great deal of them—e.g. words, thoughts, feelings and perceptual objects—are relatively transparent in their differences, even when it remains obscure how they fit together. One does not need to perform a dissection of the human body or brain in order to distinguish these aspects of language, as one does to uncover the physiology of speech, for example. At the same time, similar to the more “animal” impulses and instincts like hunger, digestion and parental attachment, speech is a distinction of normal human beings, separating them from the plants and animals but not requiring any uncommon capacities or environmental conditions, or even a meagre concern for how its complex of components fit together: “we are always speaking […] even when we are not particularly listening or speaking but are attending to some work or taking a rest. We are continually speaking in one way or another. We speak because speaking is natural to us” (187). Language is distinct from concentrated thought and attention, and its more or less unbroken operation in human life continues even in their absence—to the extent that, if the unreflective or unreflecting could or would reflect, they would see that they were speaking. Language is indefinably close to the “nature” of human beings: we speak long in advance of our awareness of that speaking, even longer before we have the chance to theorize about its generic properties or deeper significance, and again more or less indifferently past the conclusions developed out of the latter reflections.

Heidegger’s approach to language is bound up with the tension that is fundamental to the statement that “Language speaks” (188). The speaking of language must be responded to apart from the thoughts, images and concepts that it evokes and which determine it in turn. But the speaking of language cannot be isolated from the spoken words in which it invariably comes to completion; or from the thoughts, feelings and concepts with which it is inextricably bound up. Language is itself, but never itself alone. In Heidegger’s own analysis, language is said to speak thoughts, feelings, things, the earth, the sky, mortals and divinities. It would be thoughtless to reduce any of these to purely linguistic entities, even if they cannot be thought without being spoken (of), and even if, like humans, they are what they are only on account of their capacity for speech. For the proposition “language speaks” indicates that the presentation of things accomplished with language is proper to speech rather than perception, memory or hallucination—and we must remain mindful of all of them in their differences. It is the mode of presenting peculiar to language that we are trying to get at while remaining aware of the necessity of approaching it in its togetherness with what is presented, and with other forms of presentation.

In order to reflect on the words “language speaks,” we must respond to the speaking of some language in our own way, rather than simply seeking to comprehend (in the sense of apprehending or taking in hand) what it is that Heidegger is saying. For Heidegger’s discussion involves an attempt to respond to language—i.e. to something spoken—in a manner that corresponds to the speaking of that language, rather than exhausting its meaning with his own thoughts and interpretations. Speaking does not speak itself alone—which is to say, it speaks to the hearing, and can be heard in many different ways. For hearing is necessarily itself a kind of speaking: “in what is spoken, speaking gathers the ways in which it persists as well as that which persists by it—its persistence, its presencing” (192). Obviously, this manifold speaking cannot be heard simply in the manner of an historical occurrence in which the thoughts, feelings and experiences of a particular speaker are given external expression. Hearing reaches out toward what is spoken in anticipation of its communication, and is thereby also immediately inclined toward response, i.e. speaking.

“Ether” is a word familiar to the ears of the majority of English speakers. In ordinary usage it can mean the air, the atmosphere or the heavens. In its adjectival form, “ethereal,” it can mean otherworldly, ghostly, gaseous or immaterial. The more or less synonymic or anyway closely associated words are abounding. As soon as one begins to describe the ether, a spectrum of meanings ranging from the concrete to the symbolic to the altogether obscure are placed side-by-side. One is reminded, somewhat disconcertingly, how baffling and strange the familiar can sometimes be. At the same time, this is just a word, and it is sometimes the case that a word issues from little more than a fanciful unreality in the human imagination, or else as a merely useful conceptual construct, meaningless in itself. However, it may be the words that are difficult to place within the realm of representational meaning that are of the greatest interest to a discourse on the speaking of language.

Electromagnetic waves were first predicted mathematically by James Clerk-Maxwell in the 1860s: “both light and electricity, Maxwell showed, resulted from vibrations in the ether; they differed only in the rate of vibration” (Czitrom 62). Clerk-Maxwell was concerned with the phenomena of light and electricity and invoked the idea of “the ether” in order to explain their material basis. The ether was not something Clerk-Maxwell observed, but is said to have provided him with an explanatory ground for the material processes underlying phenomena observable to the ordinary human eye: “although the notion of a mysterious, all-pervasive ether later became discredited among scientists, it served Maxwell as a convenient fiction to help explain the presence and behaviour of electromagnetic waves” (Czitrom 62). The phrase “convenient fiction” circumscribes the concept of ether within certain parameters of meaning. We are quickly drawn toward the conclusion that the use of the idea of ether was incidental to the matter at hand, which concerned the real generation of the phenomena of light and electricity through the mathematically predicted occurrence of electromagnetic waves. The word “fiction” suggests intentionality: it says that Clerk-Maxwell invoked the immaterial idea of ether in order to bring into relief, like coloured light on a white projection screen, the more substantial theoretical entity of wave-vibrations in the air.

But we must still account for the idea’s placement among the other so-called inventions of the human imagination as well as the conditions of its generation, as long as we remain set on explaining it in terms of some fictional unreality it presents—for it is said that the fiction, itself simply a convenient trope, is brought forward to explain what is too complex to be accessed directly and therefore can only be reached through a simplifying medium. Thus, it should not be too difficult to determine the grounds on which this fiction was produced. We can, for example, spell out its historical determinations. In fact, both the word “ether” used by Clerk-Maxwell and its general conceptual associations connect it in a remarkably little-altered manner to ancient Greek thinking of around two and a half millennia before. In or around the sixth century BCE, the Milesian philosopher Anaximenes theorized about what he called “a?r”:

Anaximenes … like Anaximander, declares that the underlying nature is one and unlimited [apeiron] but not indeterminate, as Anaximander held, but definite, saying that it is air. It differs in rarity and density according to the substances <it becomes>. Becoming finer, it comes to be fire; being condensed, it comes to be wind, then cloud; and when still further condensed, it becomes water, then earth, then stones, and the rest come to be from these. He too makes motion eternal and says that change also comes to be through it.” (Curd 19–20)

The stuff of nature—what we now sometimes call elemental matters and other times phenomenal appearances—is said by Anaximenes to result from the rarefaction and condensation of a single underlying nature, a?r, which is invisible “when it is most even” (Curd 20). We can easily draw parallels between the varying levels of condensation and rarefaction of the a?r and Clerk-Maxwell’s later conceptualization of electromagnetic phenomena as resulting from the varying rates of vibration of a single ether; or between the all-encompassing nature of the ether and the cosmogenetic and cosmological characterizations of a?r. That is, it is quite possible to make hypotheses about Clerk- Maxwell’s way of constructing ideas, concepts and images—or what Heidegger calls the “act of imaging” (195)—as well as his use of the word “ether” itself within the historical process through which both thought and language are transmitted.

However, the more we try to locate Clerk-Maxwell’s conceptualization of the ether within its historical context, the more difficult it becomes to play it off as a mere fiction, primarily because it falls within one of the more ancient, enduring and importunate strains of human conceptuality, fictional or otherwise. In Anaximenes’ view, a?r is both the cosmogenetic and cosmological principle underlying the entirety of existence—to borrow Heidegger’s terminology, the element of both its presencing and its persistence: “just as our soul, being air, holds together and controls us, so do breath and air surround the whole kosmos”; “the principle is unlimited [apeiron] air, from which come to be all things that are coming to be, things that have come to be, and things that will be, and gods and divine things” (Curd 20). From Clerk-Maxwell’s perspective, on the other hand, the ether becomes a valuable concept precisely where the existence of gods loses its tenability within the empirical edifice of the epoch of scientific reasoning. From that view, the concept is established within the highest realm of scientific progress. And yet, Anaximenes had already accomplished a comparable—which is (emphatically) not to say identical—step back even before monotheistic religious beliefs came to hold sway. Despite the myriad advances in mathematics and physics at play in Clerk-Maxwell’s thinking, the ether comes forward as more of an echo of a thinking long past than anything else.

The paradox surrounding the similarity between the ether and a?r results precisely from the enormous differences which otherwise surround the thinking of the two. In each case, the concern is with the tangible, visible and/or measurable on the one hand, and with their underlying conditions on the other. But for Anaximenes, the a?r is what brings things into becoming, and it is indistinguishable from that becoming; while, for the theorists of electromagnetism, ether is what allows things to be, persist, and act as what they are to our knowledge. In that sense, it is self-effacing in its obscurity, serving as the mysterious background of the known without enveloping it in the mystery.

At the same time, we cannot yet go so far as to suggest that the so-called fiction is of negligible importance to the science, a mere accident of history whose significance reaches only into a more or less incidental realm of the popular imagination, beside which science follows its own necessary progress. This is so even though, from a certain view, the ether never added anything to the knowledge or understanding of gravity, light, heat or electromagnetic waves. Clerk-Maxwell predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves mathematically, without providing any substantial speculation on the condition of the ether; correspondingly, the comprehension of the thing discovered does not depend on a familiarity with the historical context, from Anaximenes to Clerk-Maxwell, of its initial discovery. When the issue concerning electromagnetic phenomena was practical and technical, one did very well without so much as mentioning the ether. For example, Guglielmo Marconi was an early innovator in wireless telegraphy, but he was concerned primarily with sending coded messages across oceanic divides in a really practical manner; he was concerned with gravity, light, heat, electromagnetic waves—and the sound of spoken language transmitted to and from telephone and radio terminals. In this context, the question becomes why the ether had to arise in the scientific imagination at all. On top of the “echo” noted above, the science of electromagnetic waves seems to stand as an alibi or occasion for the reinvigoration of a thinking long past—an occasion taken up eagerly into the beginning of the twentieth century. Importantly, a closer investigation suggests that this thinking is inextricable from its manner of speaking.

Just because the ether seems so discordant and misplaced (what some would call a scientific naivety), it is not to be easily dismissed. The characterizations of the ether are fumbling and obscure, usually resulting in almost comic triviality. For example, despite the qualification of the ether as “subtle” and “incomprehensible,” it is given distinctly material qualifications derived from the most readily available empirical phenomena. The ether is called a “substance” that “penetrates” the observable matter of nature (Lodge quoted in Czitrom 64), and the image provided of matter “embedded” in the ether is analogous to any number of common experiences, such as the suspension of stones in mud or earthen particles in water. The ether brings things together and holds them apart, facilitating their interaction. But the ether is nothing distinctive in itself. It is posited as a provisional concept with the caveat of extreme uncertainty: “can we smell the ether, or touch it, or what is the closest analogy? Perhaps there is no useful analogy; but nonetheless we deal with it, and that closely” (Lodge quoted in Czitrom 65). The ether is understood by way of analogy, and this analogy is useful up to a point, but ultimately any way of imagining it is untenable as a description of how things really are. In other words, the comprehensive concern underlying all concepts of ether is perpetually in the mode of speaking toward the phenomena of experience; it never comes to rest in the spoken (i.e. its speaking is never finally spoken for).

It is tempting to say that the theorization of the ether leaves things be, but this is an unhearing, surface-level approach if it takes that “leaving be” as a trivial, passive affair. For, first, this is where language is the least straightforwardly bound up with what is not constituted in the speaking of language—that is, distinctive perceptual or conceptual things that it represents—while simultaneously reaching out toward the entirety of empirical phenomena. Theorists of electromagnetism, in their treatment of the ether, quickly move from speaking all things all at once to speaking nothing: here, it is the “mysterious and all-encompassing” universal ground; there, it is a mere “convenient fiction.” It can be said that the ether is constituted only in this diverse, often contradictory, seemingly trivial speaking. Moreover, it is precisely where the language of the ether seems to speak nothing that it is actually labouring to speak toward all things at once, or that it has given up such a labour. Both Anaximenes and nineteenth century practical and theoretical scientific discourses invoked the a?r/ether in relation to phenomena in which they took a generally concrete interest. Even in the obscure terrain of the ether, “language speaks” in regard to thoughts, feelings and experiences; it does not invent fictions out of the ether, but places concrete phenomena within the ether. Why is a fiction needed to support a science, especially as the background of all theoretical and empirical phenomena? The fiction supports the concretization of facts and recedes into their historical background—literally the background out of which it is said that nature has finally emerged directly, as a matter of fact. Only after the putative emergence in fact is the support subsumed (or overwritten) under its matter and thereby demoted to the status of an historical curiosity.

It is the speaking of language that is deemphasized under the tangible development. Heidegger makes a distinction between speaking and the spoken. All speech comes “to completion in what is spoken”; but “the speaking does not cease in what is spoken. Speaking is kept safe in what is spoken” (191−192). We can think of this distinction in terms of the relation between the isolated act of speech and the shared conditions of the speaking community in which it is constituted as meaningful. The community shares and circulates associations between sounds, conceptual constructs and perceptual and affective experiences. The individual speaker communicates only by applying the common codes (semantic, syntactical and grammatical) in relevant social contexts. On the other hand, the community consists only of the aggregate of individuals who give the system currency through specific acts of speech. It is only insofar as speaking is always occurring (i.e. in particular instances) that the general conditions through which it operates are maintained and transmitted through time. But the system is then inextricable from the aggregate of specific acts of speaking which necessarily come to completion in the spoken.

This is a way of understanding the complex operation of language across time. Now, even though this description yields a conceptual interrelation between calling and responding similar to that invoked by Heidegger, it remains oriented toward the “description and explanation of linguistic phenomena” (191). However correct, it does not attend to the speaking of language itself; despite its appealing paradoxical character and amiable positioning of the individual in constitutive relation to the community, it attends to the logical functioning of language—giving it a formal schema—rather than its “persistence, its presencing” (192). It thus risks distracting from our focus on the speaking of language. (But is it not precisely the “paradoxical” nature of paradox that it distracts us with its pregnant confusion and in so doing calls us to attend to the limitations of our own thinking?).

It seems that we are unable to approach the speaking of language itself through the tracing of its historical recurrence. However, what about when the speaking resonates precisely in the form of an echo? For instance, the words “language speaks”—Sprache spricht—echo themselves and produce their own peculiar resonance and recurrence. We cannot locate that resonance in either one of the words, but quickly see that one follows the other only by way of responding and appealing to its similarity in turn. Each is there, in and of itself, for the sake of, in response to, and on behalf of the other.

Heidegger says that language speaks as “language, speech” (189). At the same time, it does not speak as language alone, since it always concerns contexts of thought, feeling and perception in relation to culturally constructed meanings. But speaking is not only the historical transmission of meaning: “the speaking does not cease in what is spoken. The speaking is kept safe in what is spoken” (192). We see this especially in the case of the broad historical gap between Anaximenes’ a?r and Clerk-Maxwell’s ether: they are remarkably similar, but what is surprising is that this similarity occurs despite the drastic shifts in meaning between the different contexts in which they are applied. The resonant echo of the ether is not merely historically-culturally constituted—it rather persists relatively intact (if such a characterization can be made of an echo) despite broad-scale historical shifts. But we must note well that such persistence is not at all a passive affair, a timeless self-relation such as we might imagine of a stone. It is not possible in the case of either Anaximenes or Clerk-Maxwell to pinpoint the ether as either ground or result, whether in its conceptual figuration or its function within reason. We can make obscure assessments of its character, invoking its “atmospheric” quality within the cosmic worldview, finally being dismissed as a “mere fiction” concurrently with the epochal privilege given to the rational object of empirical and practical sciences. But we are still left asking what the peculiar appeal of the ether was, such that it was continually spoken without ultimately getting anywhere except back to its own amateurish and fumbling but enthusiastic manner of speaking. The pseudo-conceptualization of the ether spoke toward the ultimate unity of the cosmic phenomena, but only insofar as the ether was thought to play an actively unifying function in the ongoing play of diverse cosmic forces: “we must regard it as the one universal medium by which all actions between bodies are carried on” (Lodge quoted in Czitrom 64).

What is a medium? A medium goes between; for example, ether penetrates “between the particles of ordinary matter” (Lodge quoted in Czitrom 64). The medium connects things, but it also holds them apart. What transpires through a medium does not happen all at once—it is mediated rather than immediate. But the presence of a medium does not signify only that one thing happens after another. Rather, the simplest way of designating the presence of a medium holds both that one thing happens before another, and the other happens subsequent to the first. Whether in time, space, or any amalgamation the two (e.g. causal nature), a medium holds everything in its place in the context of its relations. It goes between so as to unify what belongs together (atoms of matter, events in time), but also leaves apart in their differences those same things.

Language is often said to be a medium or means of communication in that it goes between speakers, allowing them to share thoughts, feelings and experiences, or correlate their actions and thereby work as a unity. However, as opposed to electromagnetic waves, which are sent by a transmitter and received by a receiver, language is predicated on a nonlinear appeal-response relationship: to speak is simultaneously to respond to a preceding context of meaning, to appeal to the familiarity of another with that same context of meaning, to appeal to the other’s readiness to respond, and to respond to one’s own expectation of the other’s response, which, if it comes, is itself heard as an appeal for a response—for hearing is necessarily also a kind of speaking.

“Language speaks.” It is variously called a means of expression, a medium of communication, a mode of questioning or interrogating the real, a function for drawing connections, making distinctions, assigning value and giving names, and so on. The invention of fictions, the recording of events, and the abstraction of logical systems are modes of spoken language; their constructions divert language away from the originality of its speaking and toward the interests and desires of the speaker. But “speaking does not come to rest in the spoken”—that is, as long as we are in the domain of language, we will remain compelled to constitute and reconstitute the identity of the spoken by virtue of our original relatedness with speaking, a relation to which the differentiation of the spoken inheres despite its provisional displacement. Whatever privilege we try to accord a thing, the speaking of language issues forth as the medium through which such a thing is held together and presented in its persistence. The thing is not a result of language insofar as language is a mode of responding and attending to, as well as presenting things in their own differences. At the same time, there is nothing outside of the immediate relation with language, which selfeffacingly relates the thing, carrying it along; conversely, language is perpetually solicited for the sake of preserving the tensed identity of such a result.

Language is an overcoding that calls things out of their bear immediacy, calling them into the mutual togetherness which constitutes a world. Only as such a restless calling and responding can language at one time bring out the interconnected fullness of the world of things, and at another time fall into the impoverishment of undifferentiatingly overdetermined abstraction. It is this dual effacement of the original speaking of language that gives a?r/ether such a strange role in the history of speaking. Heard correctly, the ether speaks the precariousness of speaking: the resonant, overcoding echo alternately dismissed as a trivial abstraction and subsumed under the apprehended concretion of things.

“Language itself is—language and nothing else besides.” Language is a unique, incomparable phenomenon: any way of explaining it in reference to functions, causes, effects, and the like is necessarily accomplished through a speaking that precedes such explanation as its condition and exceeds it in turn, relatively indifferent to whatever it is that such explanation has accomplished, whether in regard to it or for some other purpose. Therefore, language will always have to be approached, responded to, or addressed on its own terms—that is, by recourse to, on behalf of, and through a partial determination of its original manner of speaking. At the same time, language cannot be isolated, for example, to the identity of the word. The phrase on its own terms merely gestures as a sort of reminder toward the sure but elusive domain of language, while acknowledging that language persists through the irreducible differences of its relations with thought, perception, logic, imagination, and so on; in such freely given diversity the differences are easily forgotten, so that the reminder is often necessary (maybefreedom is drawn with lines and circles insofar as we are never either/ever neither trapped within a circle or/norstrung out on a line, each thanks to the other—and each because, imagining we are positioned somewhere on acircle, or on a line, it is impossible to say definitively on which one we currently abide, and therefore impossible todetermine the proper manner of comportment: giving thanks to the one for its gift to the other or for the respite itprovides from the other; questioning their appearances; cursing ourselves for such myopia; thanking ourselves forthe same; questioning whether there are really two such forms, whether there might be less or more, and whether wehave a clear sense of their shapes and trajectories; questioning whether there is in fact a distinction between themanner and the way, and what matter the distinction is, e.g. whether it is itself a way or not; lending the force ofwill to the confusion and thereby inverting the sense of lack; etc.). Thus, Heidegger says that the language of poetry and thinking “meet each other in one and the same,” but that such sameness is “the belonging together of what differs, through a gathering by way of the difference.” Poetic language and thinking belong together in a way that is original and essential to both, such that we cannot speak of poetry without finding ourselves already, more or less explicitly, in the domain of thought, or of thought without finding ourselves already, more or less overtly, in the domain of poetry (e.g. “all language is metaphor”). Already at the beginning, both speaking and thinking have arisen of themselves, and each on its own through its invocation of the other and in response to the invocation elicited of it by the other.

It is not only that language speaks things; it speaks the diverse spread of worldly things, bringing them together and holding them apart in their irreducible differences. It speaks the spontaneous necessitation of difference itself, the perpetual re-beginning of the speaking that is also a hearing and the hearing that is also a speaking. There is no moment (e.g. of time or causal necessity) or aspect (e.g. of a thing or relation) that can abide in privilege insofar as every moment qua abstract becomes active only where it is not, i.e. in the relation out of which it is abstracted. It is speaking (vis-à-vis the spoken) that abides originally in such inextricable relationality.

Perpetually reconstituted in the abstract moment of its own necessitation, human thinking cannot be privileged; it can, and must, only give privilege. And yet, it is constantly trying to short-circuit that order: to be the privilege it can only give; or, what amounts to the same, to make the giving of privilege pass over as the absolute principle of the thing so privileged. In other words, to privilege is not a transitive verb, but we try to appropriate and interpret it as such.

The idea that “man speaks” is conventionally taken to mean that humans elect to speak, coming to the decision by way of thought. A distinction is placed between man (i.e. the rational animal) on the one hand, and the act of speech on the other. In everyday thinking, this results largely from the fact that we are aware of thinking about speaking in advance of the particular words that are selected (a peculiar kind of ‘after X, therefore because of X’ fallacy/temptation). On the other hand, in studies of language which attempt to give linguistic expression to the characteristics of language itself, this is a necessary assumption. We (universal, rational beings) could not bring ourselves to say anything about language if it were impossible to put some distance, whether real or imaginary, between our thoughts and the words we use. While nobody would deny that the capacity for language develops and functions interdependently with the capacities for thought, reflection and memory, when it comes time to study the universal aspects of language, we must suppose that it is possible to keep language at a distance from rational thought, so that the latter is capable of abstracting from the “natural,” unabated procession of the former. And the fact that thought can abstract from such a procession and thereby produce a result, i.e. out of the affectation of such a rational distance, leads us to invest a superordinating faith in reason’s detachment from its objects, and project it as such an ideal. (Maybe reason is a species or partial development of faith insofar as the positing of the object— through learned methods, concepts etc.—coincides with the possession of it, rather than, as in faith proper, having the “object” first and positing it second).

And so, we are ill-disposed to see the manner of analysis selectively performed in such modes of rational thinking, and that such selection tries to speak for language instead of attending to the speaking of language. We fail to see the selecting that constitutively goes into the selected, and we thereby remain ignorant of our object—we think we have it, but really we are straining just to catch a meagre glimpse through the interposed abstract perspective. It is in the same way that even when we begin to view human rationality as having its own peculiar manner of occurrence, we respond to it or speak for it in the same way we would a simple cell, or a computer; just as, when we study emotional intelligence, we place the emphasis on intelligence and speak for and respond to it in the same way we do rational thought, which we speak for in the same way we do computational devices, etc. We acknowledge that they do different things, but we address that doing with an undifferentiating, indifferent manner of response. The (sometimes unwitting) assumption underlying such an approach is that whatever differences there are between what each does, the doing is effectively the same insofar as its significance is to produce a result. We then abstract the result from the specificity of its thoroughgoing process.

The abstract conceptions of time, reality and necessity present a paradigmatic example. We treat the concept of necessity abstractly, as if all that is required is some fundamental formula that covers all manners of action and reaction, persistence and alteration. But none of these formulae can be adequate to our sense of necessity—for necessity would not be the essence of change if it were not coextensive with that change. In other words, the changes that occur in accordance with necessity simultaneously change the very nature of that necessity, and therefore of change.

The abstract concept of necessity posits the predictability of a thing or state of affairs in advance of its happening or, inversely, the predictability of the consequences of a given thing or state of affairs. In short, it presupposes the regularity of a thing’s relations, such that all the variables on which its fate depends are readily accounted for. The scientific object, then, is one that is determined by regional specificity and maintained within the parameters of a given system with repeated cycles of activity. The scientific object is an abstractable objectivity only on the condition that its environment—its comprehensive system of relations—is itself an abstractable objectivity composed of abstractable objectivities, each variable reciprocally held in place by the mutually exerted forces of the others. But then, how do we characterize the necessity of the forces driving the system? We can of course say that one thing follows on another in accordance with the perceived pattern, invoking the inductive knowledge we have attained through empirical research. We then further remark that there must be some properties inherent to the elements in the relation that necessitates their interaction in such a way that guarantees the recurrence of the abstractly observable moments of the cycle. In fact, whether we draw connections between one cycle and the next, one entity and another, a state and the one that follows, etc., we are only filling out a more detailed picture of a general pattern that has already been perceived. The spontaneous perception of a pattern has turned into the methodical perception of patterns. But necessity is no more contained in the abstract correlation of discrete states, entities or cycles than it is in the initial discernment of a general pattern, e.g. a day. Even as we fill in more and more knowledge of the details, there is a kind of naivety in every step forward. For the more attention we give something, the more we view its necessity through the abstract mode of perception implicit in the initial address of the object as one favourable for scientific investigation. The formulation of a problem or question not only determines the qualitative approaches to or acceptable forms of its solution or answer; it already arises in the form of an answer in that it concerns a contingency that is addressed abstractly. It is then unsurprising that the corresponding answer is always unsatisfactorily abstract—that is, that it contains the limitation of the initial mode of address.

We tend to place necessity between the successive occurrences of independent moments, such that the one is conceived as following of necessity in accordance with the determinate trajectory of forces inherent to the first. However, the idea of a “moment” is already an abstraction from the flow of time, constituted in its differentiation from, and therefore its relation to, other “moments” abstracted from that flow. That is, this view of temporal succession already presupposes a complex of abstracted moments, each of whose necessity is placed outside of it in the moment which precedes it, and so on indefinitely. The paradoxical result of privileging a conception of the abstracted moment as the absolute object to be explained is that such abstractions qua abstract really are contingent upon the whole complex of abstract moments which precede and succeed them. But when we impute a simple reality to abstract moments, we come to the contradictory result that each is passive in its dependence on the possibility contained in the preceding moment but active in its own necessitation of the moment that follows, and thus active only where it is not.

We can respect the momentously novel logic of the abstraction of linear temporal necessity while maintaining reservation in regard to its coherence and significance. For, in a very real sense, simply to conceive of the “moment” raises us above the immediacy of time—we can not only identify patterns, but we can make our very actions more abstract and economical, whether those actions involve productive labour or unproductive thought. On the other hand, this does not mean that the reality of the future is immediately contained in the possibilities inherent to the present—it is not the “reality” of the future that is predictable in advance, since predictability and prediction are definitively abstract. For its part, abstraction is only one aspect of thought that is differentiated out of the more diffuse specificity of its spatiotemporal flow. The abstract logic of thought substantiates its own spontaneous necessity at the very moment that it has posited the impossibility of spontaneity. As a concept, “necessity” draws our abstract logic toward the specificity of the thing; but that specificity itself appears only in the crudely functional abstractions of linear temporality, vectored and pixilated, differentiated out from the spontaneous necessitation of its more comprehensive ground. Even on sheer practical terms, anticipating: the contingencies of phenomena according to local and global interactions; the contingencies of the observer and its methods, conceptual constructs, and lines of communication; and their shifting interactions, destabilized according to the predilections of particular observers, on the one hand, and real phenomena, on the other—the idea of necessity is a manifold construct, an investment of resources, a synthesized image, and an accomplishment with its own immanent stakes (e.g. the valorization of its investment).

In the era of neuroscience, we have accepted the concrete or “plastic” aspect of consciousness, and yet we treat it as concrete in the sense of material objects—which are effectively the logical objects of abstract reasoning— just as, when we accept the ineradicable, immanent investment of the conditions of the observer in the observed, we have a hard time treating this as anything other than a correctable refractivity, or, conversely, as simplistic relativism. But, seeing as there are many different kinds of observation and many different kinds of objects, each with its own manifold of aspects, it is sensible to account, practically and theoretically, for the variety of approaches possible for empirical study—its living methodology and conceptualization. The logically extended empiricist standpoint is neither a statement of the hopelessness of empirical investigation (i.e. “we cannot know reality as such”), nor of its simple and inevitable limitation (i.e. “we can only know in this way”); rather, it indicates that there are as many forms of knowledge as there are manners/styles/types of observation, that the knowledge attained through observation (including its guiding impulses and ideas—those concerning selection of object, for instance) is inextricable from the specific act—and that there is therefore incoherence and contradiction in not constantly taking stock of such conditions. Such incoherence and contradiction cannot be “solved”; they are generic conditions out of which observation arises, and which all observation serves to directly shape in turn. Observation is never without its share of suggestive obscurity: it is quite literally made.

At the same time, observation has no fundamental ground or beginning. What it does have is a manifold of irreducibly distinct principles (i.e. that cannot generate or account for each other). Perhaps the most infamously elusive example is the medium (e.g. the faculties, the senses): self-effacing, appearing like a freely given gift that simply allows things to be (conveyed and received) as they are, and yet it is just there—in regard to the absolutely unique, neither a form nor a content but an irreducible principle—that our interpretive tendencies toward reduction are most tempted. Taking light as our example (the sun and the media image would make for an interesting comparison), we can say that it invites/incites the most varied interpretations—formed around the phrase “for thesake of”—but finally accepts none of them. We also struggle with the temptation to say for the sake ofwhat language, vision, hearing and so on, exist! And it is precisely the most plausible answers—e.g. genetic selfpreservation— that are the least convincing. Within local conditions, we manage to say how, e.g. grass survives, growing and propagating. But all of this is built off of some apparently very basic (simply lived) presuppositions— e.g. there is grass, or there is light—comprised of irreducible relations to which logical explanation simply does not apply. Ubiquitous, unique, primordial and absolute in speed and quality, but at the same time, as Nietzsche’s Zarathustra remarks, “You great star, what would your happiness be had you not those for whom you shine?” (121). Surely, we cannot make any kind of beginning by recognizing these aspects of the sun, especially since it cannot even make for a beginning of itself (but is rather generically, parabolically constituted through the specific aspects of its differences). Which is as much as to say that we cannot make any kind of beginning—we can only make a beginning of something else, or something else of the beginning. But it always lends itself to this something else. Thus, we begin with the accomplished simplicity of the abstracted moment.

Much of Nietzsche’s work is methodically committed to the paradoxical spontaneity of human thought, to the extent that ethical, metaphysical, epistemological and aesthetic concerns are never treated without a more or less immediate invocation of the others. All of these appear as modes of interpretation with simultaneously necessary and limited formative roles in thought: “There is only a perspective seeing, only a perspective “knowing”; and the more affects we allow to speak about one thing, the more eyes, different ones, we use to observe one thing, the more complete will our “concept” of this thing, our “objectivity,” be. But to eliminate the will, altogether, to suspend each and every affect, supposing we were capable of this—what would that mean but to castrate the intellect?—” (GM III 12). The implications of this view of perspectivism are ambiguous. One the one hand, every perspective is both inherently limited by its own capacities and, inversely, dependent on the perceived—since, just as certain cognitive and sensory conditions must lay in the percipient, those conditions must respond and therefore, at least to some extent, conform to the conditions of the perceived. For example, the fact that the intellect must somehow compensate for its abstract distance, must somehow both measure that distance and fill the void designated therein, necessitating further inventorying operations in turn. (Consequently, in response to our earlier remark that atomistic matter is a projection of the abstract perspective, we can ask: but what is that perspective projecting? i.e. what conditions and constraints is the abstract eye responding to?). On the other, perspective is a kind of self-positing relation to a thing perceived, such that it is always more than just this viewpoint—perception always at least tacitly implies the excess of perspectives folding over one into another. In other words, the limited standpoint of the observer is also and for the same reasons the site of possibility (i.e. of more perspective).

What is added to our initial story-image, particularly to its “human” developments, in light of such speculative insights? When cosmic regions come together and separate off from other regions, pockets of density form, clusters of compatible matters group together, regularity is established in the interactions animating the cooccurrence of one thing and another, the incidents of radical instability and spontaneous development settle into cyclical patterns of change (e.g. rarefaction and condensation). It is tempting to say that chaos evolves into order insofar as the incomparable and unique give way to the repetition of patterns, the mutual gravitation of the compatible, the mutual dispersion of the incompatible, and so on. At the same time, settlement and systematization are concurrent with spontaneous change and development. This point might be illustrated through several domestic (i.e. microcosmic) aphorism-images (each, being immanent to the cosmic scale, with its own peculiar relevance): “one never moves into a house without simultaneously preparing for the move out”; “childbearing is a funerary preparation”; or “the life of the marriage right is in the drama of the divorce.” (We might look to the works of SamuelBeckett in order to set out on a way of properly responding to the vital geometry of such complexes. Take this germof an early poem, called “Gnome”:

Spend the years of learning squandering

Courage for the years of wandering

Through a world politely turning

From the loutishness of learning.)

We invariably think of systems in the sense of unions and contracts sanctioned by nature from time immemorial, omitting the principles of emergence, continuous immanent alteration, and dissolution—omitting, in addition, that there was never a “moment” without its own immanent configuration and a consubstantial necessitation, that it is impossible to privilege or ignore either the immanent configuration or the principle of succession, since each is constitutively momentous in the abstract logic of the independent moment. Each moment is differentiated out of and exceeded by a movement that is radically but interdependently different from its own abstract logic.

Generally speaking, there is no aspect of human life not determined by the irreconcilability of opposites, every union being in some sense bound up with the overdetermined rigidification of a soluble inequality. Difference, change and uncertainty are regulated on personal, interpersonal and institutional levels. The coherence of any system depends on the repetition of difference and change, rather than the self-identity of an artificial union. Identity is precisely an achieved way of addressing the asymptotic approach of the different, a symptom of the coming together of opposing forces—and if statements of identity succeed, it is so only to the extent that they address the contingency of oppositions through the always selectively abstract reiteration of their patterns of difference and change.

What do we think in the concept of necessary action? The impossibility of something’s having occurred otherwise? But this takes necessity in only one dimension: the immediate present. There are only two ways of addressing this moment: as either itself and nothing more, in which case nothing can be said about it other than that it is or was, i.e. “it happened because it happened, it had to happen because it happened, it happened because it had to happen, it had to happen because it had to happen, etc.”; or else through that which precedes it and then that which follows, in which case the life (or living presence) that is lost in referring the necessity of the moment to the one that precedes it, is regained in its causal determination of the one that follows. Either way, this is wholly inadequate to our conception of what necessity qua spontaneous necessitation actually is—i.e. the immanent tendency and capacitation of mutually confrontational aberrant differences toward the spontaneous and unfamiliar— and can therefore only be diminished and bastardized by our abstractions (which, however, carry their own inner logic). According to Nietzsche we can only feel ourselves necessary in the course of adversarial relations, as against the enemy who is also and for the same reason a friend, since it is in the confrontation of difference that one’s powers are actualized—and the confrontational space of difference is therefore in itself the space of appearance, the stage on which reality takes place. It is maybe in this light that we should interpret Nietzsche’s aggressive relation to his food, which is said to have been the cause of perpetual digestive troubles, but which Nietzsche was, possibly forthat very reason, drawn to by his interest in the aberrant force of his spontaneous necessitation (e.g. the affectiveabstract necessitation of interpretation). The principle of spontaneous necessitation requires that we take account of (e.g. by participating in or seeking out such phenomena) the tense together-apartness of the aberrant case, as distinct from the conception of temporal necessity logically extracted from abstract systems, cycles and repetitions. But human experience, including the concept of necessity that we bring to bear on it, invariably consists in and persists through its abstract element. The significance of the concept of necessity, then, is that it is impossible to realize on the conceptual plane—it is inherently inadequate to its own sense, and is thereby an interactive, procedural concept. We cannot provide an abstract concept of necessity as such, since every reality must follow its own necessity. The concept of necessity can only point the way to the necessity of its objects by finally relinquishing its hold on them. Such feeling responsiveness must accordingly be built into the concept (keeping in mind that to respond is always also to speak).

To repeat: in accordance with the cosmogenetic principle of the spontaneous necessitation of the irreducibly different, Even the more or less stable entities at play in our reality must be conceived differently: instead of being stable in themselves, their stability coincides with the principle of spontaneity through which they developed and, along with the developed parameters, continue to develop. Their change over time and even their periods of stasis or rest are constituted through a repetition or endurance of the interactions immanent to the developmental event. Their endurance involves a micrological continuity of the spontaneous interactions characteristic of the cosmogenetic event. Moreover, there is no telling how or when some interaction internal to this “system” or between it and another—which may be similarly unique or immanently related through a kind of marginally porous border and/or cosmogenetic lineage—may set off another spontaneous cosmogenetic event. If in order to appear we must be necessitated, and in order to be necessitated we must come together in the apartness of the irreducible difference, then such cosmogenesis is already occurring, as by divine ordinance. And it occurs, not in spite of, but consubstantial with the repetition of the old and familiar, defamiliarized and familiarized anew times over. For what persists past its coming together never finally subtends the formative occasioning or instantiatingforming of that earlier event.

For example: All observation is immediately determined by its own conditions: this highly generalized proposition has a history—to the extent that it is tempting to suggest also a prehistory and a post-history—varying both between and within different disciplines of thought. One might even call it a universal of the human condition that the contingency of perception (as well as interpretation, argumentation, communication, etc.) must be learned again and again—or, conversely, that every particular perspective embellishes and thereby implicitly marks its own difference in relation to every other. We could call perspectival bias self-effacing or ignorant by default, if it were not that such charges are distinctly evaluative rather than maintaining an openly interactive relation with perspectival bias—which is, after all, a structural feature of perspective, not a defect. For the statement is effectively tautological: all observation is immediately determined by its own conditions. And yet, every observation manifests the sense of the proposition in its own way so that, in the end, we cannot remove ourselves from the continuity of its history.

Luke Schumacher