Images

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen

Fruit of the Loom

27. 10. – 8. 12. 2012

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen, Machine, 2012, Anodized aluminium profile struts, steel, plastic, 308 × 258 × 309 cm, installation view Fruit of the Loom, 2013

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen, installation view Fruit of the Loom, 2013

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen, installation view Fruit of the Loom, 2013

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen, The Same, But Different, 2012, Textile ink on t‑shirt, 38 × 49 × 3,5 cm

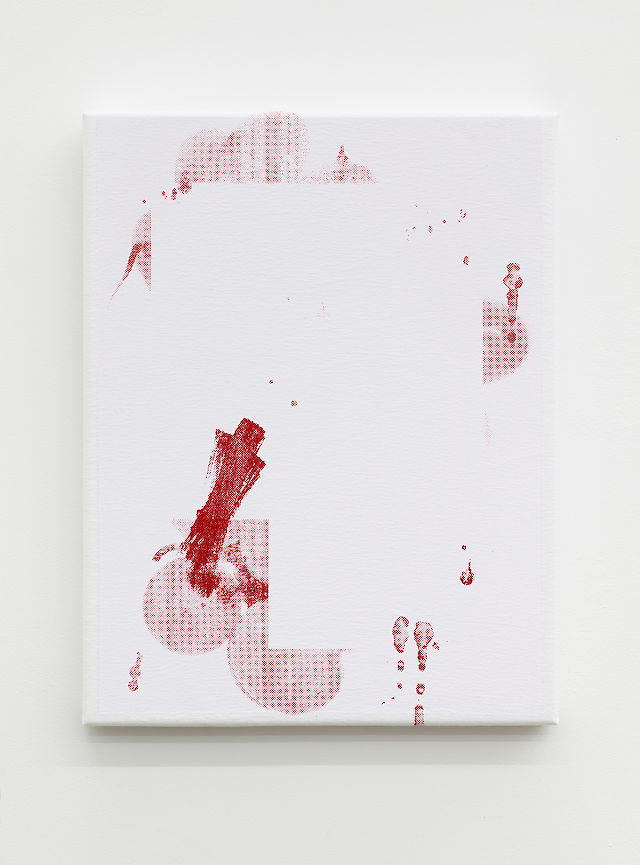

Optical White, 2012, Textile ink on t‑shirt, 38 × 49 × 3,5 cm

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen, Layers, 2012, Textile ink on t‑shirt, 38 × 49 × 3,5 cm

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen, Layers, 2012, Textile ink on t‑shirt, 38 × 49 × 3,5 cm

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen, The Same, But Different, 2012 (detail), Textile ink on t‑shirt, 38 × 49 × 3,5 cm

Press Release

It is by a loom, that the lineage of our modern computer was spun: As the first apparatus which could be programmed to carry out an automated task – that of weaving an intricate pattern into cloth – the so-called Jacquard Loom inspired the invention of the mechanic adding machine.

When in the mid-19th century an American entrepreneur coined the label “Fruit of the loom”, the stock of the machine was sprawling. Still, it was traditional values in which the evocative name was at the time rooted: resembling the biblical phrase ‘fruit of the womb’, meaning ‘children’, the textile mill owner deemed it worthy for his yield.

One and a half eventful centuries later, “Fruit of the Loom” would still ring in the ears of many, namely those of the 1990s’ MTV-generation. The metaphor originally promoting the trademark concurrently lends itself to a further spin: may “fruit of the loom” – in the modern sense – not as well be designated to a youth growing up on flickering screens and fandom?

Catchy screen-prints on best-value “Fruit of the Loom”-basics are mounted on canvas and hung on the gallery walls. Painterly marks such as brushstrokes and drips, or alphabetical letters, enhance the impression of the ‘fresh’, the individual and gestural. A strong sense of tactility impregnates Jacob Dahl Jürgensen’s images on textile – albeit they have all been entirely composed on a computer. The artist leaves the viewer’s grasp dangling: If the bold rasterization tells of the digital dis/position of the images, it just as much entwines the dotty make of the screen-print as well as the weave of the cloth. And if the varying sizes defining the textile works plead the premise of being ‘made to fit’ and ‘ready to wear’, then S, M, L and XL also assigning some of the works’ titles, altogether lay bare the blandness of such predominating categories.

Jürgensen thus pointedly reflects on the relations of the sign and the signified, an object’s intrinsic and fetishistic value, of a brand, its name and its tradtition – and on how these threads are fragmented, distorted and interwoven anew in (hi)stories of technology, sociology and economics.

In the midst of the gallery stretches a sculpture, straightforwardly called Machine. Made of aluminium profile struts (as they are often used in industry for hi-tech machines), it measures about the size of an industrial loom. Yet slightly lifted off the floor and sketching only its ‘outlines’, the Machine is at once of intriguing lightness and transparency. Rather than obstructing our view, it much more enjoins to take on manifold perspectives on the exhibition.

‘Move and it moves with you!’ The latest commercial campaign by “Fruit of the Loom” similarly suggests the incorporation of the mechanic within the human framework; a ‘becoming-one-in-motion’ as also smartphone- and tablet-ads like to bring forward. But: forget about the grid, and you may easily trip over the brute metal strut that lays the structure’s ground! Once again, a playful twist is added to the creeds of the apparel brand, for the question to be raised in Jürgensen’s “Fruit of the Loom”: Is it nowadays not rather ‘it’ that moves, and ‘us’ that ‘move with it’?

Meret Kaufmann